System Failure: 7 Shocking Causes and How to Prevent Them

Ever wondered why entire cities go dark or planes fall from the sky? Often, it’s not one mistake—but a chain reaction leading to system failure. Let’s uncover what really happens when systems collapse and how we can stop them.

What Is System Failure? A Deep Dive into the Core Concept

At its most basic level, a system failure occurs when a network, machine, process, or organization fails to perform its intended function. This can happen in technology, infrastructure, business operations, or even biological systems like the human body. The term ‘system failure’ is often used broadly, but understanding its precise definition helps us identify root causes and implement effective solutions.

Defining System Failure Across Disciplines

System failure isn’t limited to one field—it manifests differently depending on context:

- Engineering: A mechanical or electrical breakdown in machinery or infrastructure.

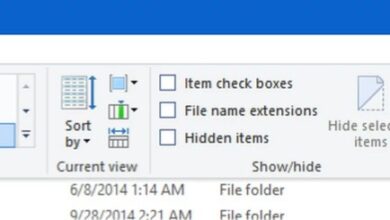

- Information Technology: Server crashes, data loss, or software bugs disrupting services.

- Business Management: Organizational inefficiencies leading to missed targets or operational paralysis.

- Social Systems: Government institutions failing to deliver public services during crises.

Each domain interprets system failure through its own lens, yet all share common threads: unpredictability, cascading effects, and often, preventable origins.

The Anatomy of a System: Components That Can Fail

Every system consists of interconnected parts—inputs, processes, outputs, feedback loops, and controls. When one component malfunctions, it can destabilize the entire structure. For example:

- Hardware: Servers, routers, sensors, or physical machinery.

- Software: Operating systems, applications, or firmware with bugs.

- Human Operators: Mistakes in judgment, training gaps, or fatigue.

- Procedures: Outdated protocols or lack of emergency response plans.

Understanding these components allows engineers and managers to build redundancy and resilience into their systems.

“A system is only as strong as its weakest link.” — Often attributed to Aristotle, this principle remains central to modern engineering and risk management.

Types of System Failure: From Partial Glitches to Total Collapse

Not all system failures are equal. Some cause minor disruptions; others trigger catastrophic outcomes. Recognizing the types helps in diagnosing issues and planning mitigation strategies.

Partial vs. Complete System Failure

A partial system failure means some functions continue while others fail. For instance, an airline’s booking system might go down, but flights still operate manually. In contrast, a complete system failure halts all operations—like a power grid blackout affecting millions.

- Partial: Limited impact, often recoverable without major intervention.

- Complete: Widespread disruption, requiring emergency protocols and external support.

Organizations should design failover mechanisms to minimize the risk of total collapse.

Temporary vs. Permanent Failures

Some system failures are transient—lasting seconds or minutes—while others result in permanent damage. Temporary failures may stem from software bugs or brief power surges, whereas permanent ones often involve hardware destruction or irreversible data corruption.

- Temporary: Can be resolved with restarts, patches, or manual overrides.

- Permanent: Require replacement parts, system rebuilds, or long-term recovery efforts.

For example, NASA’s Mars rovers have experienced temporary communication blackouts due to solar interference, but no permanent system failure has ended a mission prematurely—thanks to robust redundancy.

Latent vs. Active Failures

Latent failures are hidden flaws built into a system over time—like poor design choices or ignored maintenance warnings. They remain dormant until triggered by an external event. Active failures, on the other hand, occur in real-time, such as a pilot making a wrong input or a server overheating.

- Latent: Often organizational or systemic (e.g., culture of ignoring safety reports).

- Active: Immediate, observable, and usually tied to human or technical error.

James Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model” explains how latent conditions align with active failures to create disasters. You can learn more about this model at NCBI’s analysis of human error in healthcare systems.

Major Causes of System Failure: The 7 Root Triggers

Behind every system failure lies a combination of factors. While no two incidents are identical, research shows recurring patterns. Here are seven primary causes that lead to system failure across industries.

1. Design Flaws and Engineering Oversights

Poor design is one of the most insidious causes of system failure. When systems are built with inadequate testing, unrealistic assumptions, or insufficient safety margins, they’re doomed from the start.

- The Hyatt Regency walkway collapse in 1981 killed 114 people due to a flawed structural redesign.

- The Boeing 737 MAX crashes were linked to a faulty sensor and inadequate pilot training protocols.

These tragedies highlight the need for rigorous peer review and stress-testing during the design phase.

2. Human Error and Operator Misjudgment

Humans are integral to most systems—and also their weakest link. Miscommunication, fatigue, lack of training, or simple distraction can trigger system failure.

- In the Chernobyl disaster, operators disabled safety systems during a test, leading to a nuclear meltdown.

- A single typo in a financial trading algorithm once caused the 2010 Flash Crash, wiping $1 trillion off U.S. markets in minutes.

Training, automation safeguards, and psychological support can reduce human-induced system failure.

3. Cybersecurity Breaches and Digital Attacks

In our digital age, system failure increasingly stems from cyberattacks. Hackers exploit vulnerabilities to disrupt, steal, or destroy critical infrastructure.

- The Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack in 2021 forced a shutdown of fuel supply across the U.S. East Coast.

- The WannaCry malware infected over 200,000 computers in 150 countries, crippling hospitals and businesses.

According to CISA’s StopRansomware initiative, proactive defense and employee awareness are key to preventing digital system failure.

4. Natural Disasters and Environmental Shocks

Earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, and wildfires can overwhelm even well-designed systems. Infrastructure not built for extreme conditions is vulnerable to sudden collapse.

- Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster was triggered by a tsunami that disabled backup generators.

- Hurricane Katrina overwhelmed New Orleans’ levee system, causing widespread flooding and service breakdowns.

Climate change is increasing the frequency of such events, making resilience planning more urgent than ever.

5. Software Bugs and Code Vulnerabilities

A single line of faulty code can bring down an entire system. As software becomes more complex, the risk of undetected bugs grows exponentially.

- The Mars Climate Orbiter disintegrated in 1999 because of a unit mismatch between metric and imperial systems.

- The Therac-25 radiation therapy machine overdosed patients due to race condition bugs in its software.

Rigorous testing, code reviews, and automated monitoring are essential to prevent software-induced system failure.

6. Supply Chain and Dependency Failures

Modern systems rely on global supply chains. When one link breaks—due to war, sanctions, or logistics issues—the entire network can fail.

- The 2021 Suez Canal blockage by the Ever Given container ship disrupted 12% of global trade.

- Chip shortages during the pandemic halted car production worldwide.

Diversifying suppliers and maintaining buffer stocks can mitigate dependency risks.

7. Organizational and Cultural Failures

Sometimes, the system fails not because of technology, but because of culture. Toxic work environments, siloed communication, or leadership denial can prevent early detection and response.

- NASA’s Challenger disaster was partly due to engineers’ warnings being ignored by management.

- Enron’s collapse stemmed from a culture of deception and financial manipulation.

Organizational psychologists emphasize the need for psychological safety and transparent reporting channels to prevent cultural system failure.

Real-World Case Studies of System Failure

Theory is important, but real-world examples drive the point home. Let’s examine some of the most infamous system failures in history and what we’ve learned from them.

The 2003 Northeast Blackout: A Cascade of Errors

On August 14, 2003, a massive power outage affected 55 million people across the U.S. and Canada. It began with a software bug in Ohio that failed to alert operators to overgrown trees touching power lines.

- The initial fault was minor, but poor monitoring and delayed response allowed it to spread.

- Within minutes, transmission lines overloaded and tripped offline, creating a domino effect.

- The entire grid collapsed due to lack of real-time coordination between utility companies.

The U.S.-Canada Power System Outage Task Force concluded that outdated software and inadequate situational awareness were key contributors to the system failure. Read the full report at NERC’s official investigation.

Boeing 737 MAX: When Profit Overrode Safety

The Boeing 737 MAX crisis is a textbook case of organizational and technical system failure. Two crashes—Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302—killed 346 people.

- The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) relied on a single sensor, which could fail.

- Pilots weren’t adequately trained on MCAS, and Boeing downplayed its significance.

- Regulatory oversight was compromised due to conflicts of interest.

This system failure wasn’t just mechanical—it was cultural, managerial, and regulatory. The aftermath led to global grounding of the aircraft and a reevaluation of aviation safety protocols.

The Therac-25 Radiation Therapy Machine: A Software Tragedy

Between 1985 and 1987, the Therac-25 medical device delivered lethal radiation doses to patients due to software flaws.

- A race condition in the code allowed incorrect settings to go undetected.

- Operators saw cryptic error messages like “MALFUNCTION 54” but had no way to stop the machine.

- Despite prior incidents, the manufacturer dismissed complaints as user error.

This case is now a staple in software engineering ethics courses. It underscores how system failure in healthcare can have irreversible human costs.

The Ripple Effects of System Failure

System failure rarely stays isolated. Its consequences ripple outward, affecting economies, societies, and individuals in profound ways.

Economic Impact: Billions Lost in Minutes

When critical systems fail, the financial toll can be staggering.

- The 2021 Facebook outage cost the company an estimated $60 million in ad revenue.

- The 2017 NotPetya cyberattack caused over $10 billion in global damages.

- A single AWS outage in 2017 disrupted thousands of websites and apps, costing businesses millions.

According to Gartner, the average cost of IT downtime is $5,600 per minute—making system failure one of the most expensive risks businesses face.

Social and Psychological Consequences

System failure erodes public trust. When people can’t rely on banks, hospitals, or governments, anxiety and skepticism grow.

- After the Equifax data breach, millions lost faith in credit reporting agencies.

- Power outages during extreme weather increase stress, especially among vulnerable populations.

- Transportation system failures disrupt daily life, leading to frustration and economic strain.

Long-term exposure to unreliable systems can lead to societal fatigue and reduced civic engagement.

Environmental Damage and Long-Term Risks

Some system failures cause irreversible ecological harm.

- The Deepwater Horizon oil spill released 4 million barrels into the Gulf of Mexico.

- Nuclear meltdowns like Chernobyl and Fukushima rendered large areas uninhabitable.

- Industrial control system failures can lead to chemical leaks or toxic emissions.

These disasters highlight the need for environmental impact assessments and fail-safe mechanisms in high-risk industries.

How to Prevent System Failure: Strategies for Resilience

While we can’t eliminate all risks, we can build systems that withstand shocks. Prevention requires a multi-layered approach combining technology, culture, and policy.

Implement Redundancy and Fail-Safe Mechanisms

Redundancy means having backup components that activate when the primary system fails.

- Airplanes have multiple hydraulic systems and flight computers.

- Data centers use redundant power supplies and mirrored servers.

- Medical devices often include manual override options.

Fail-safes ensure that if a system does fail, it defaults to a safe state—like automatic shutdowns or emergency brakes.

Adopt Proactive Monitoring and Predictive Analytics

Modern systems generate vast amounts of data. Using AI and machine learning, organizations can detect anomalies before they escalate.

- Predictive maintenance in manufacturing reduces unplanned downtime.

- Network monitoring tools can flag unusual traffic patterns indicating cyberattacks.

- Smart grids use real-time data to balance load and prevent blackouts.

Tools like Splunk, Datadog, and IBM Maximo help companies stay ahead of potential system failure.

Foster a Culture of Safety and Transparency

Technology alone isn’t enough. A culture that encourages reporting, learning from mistakes, and open communication is vital.

- Aviation uses anonymous reporting systems like ASRS to collect safety data.

- Healthcare institutions conduct root cause analyses after adverse events.

- Google’s postmortem culture ensures every outage leads to documented lessons.

Leaders must reward honesty, not punish it, to prevent cover-ups and denial.

Recovering from System Failure: Steps to Restore Function

When prevention fails, recovery becomes critical. A well-planned response can minimize damage and accelerate restoration.

Activate Emergency Response Protocols

Every organization should have a documented incident response plan.

- Define roles: Who leads? Who communicates? Who fixes?

- Establish communication channels: Internal alerts, public updates, media briefings.

- Pre-identify critical assets and recovery priorities.

Regular drills ensure teams know what to do under pressure.

Conduct Root Cause Analysis (RCA)

After stabilization, the focus shifts to understanding why the failure happened.

- Use frameworks like the 5 Whys, Fishbone Diagram, or Fault Tree Analysis.

- Involve cross-functional teams to avoid bias.

- Document findings and share them across the organization.

RCA prevents recurrence and strengthens future resilience.

Communicate Transparently with Stakeholders

Trust is fragile after a system failure. Open, honest communication rebuilds it.

- Admit mistakes quickly and clearly.

- Provide regular updates on recovery progress.

- Offer compensation or remediation where appropriate.

Companies like Toyota and JetBlue have regained public trust through transparency after major failures.

Future-Proofing Systems: Building for Tomorrow’s Challenges

As technology evolves, so do the risks. Future-proofing means anticipating new threats and designing adaptable systems.

Embrace Modular and Scalable Architectures

Monolithic systems are harder to maintain and more prone to failure. Modular designs allow isolated updates and easier troubleshooting.

- Microservices architecture in software enables independent component scaling.

- Modular data centers can be expanded or relocated as needed.

- Plug-and-play infrastructure supports rapid deployment in emergencies.

This approach limits the blast radius of any single system failure.

Leverage AI and Autonomous Systems

Artificial intelligence can detect patterns humans miss and respond faster than manual intervention.

- AI-driven cybersecurity tools identify threats in real time.

- Self-healing networks reroute traffic around failures automatically.

- Predictive algorithms forecast equipment wear and schedule maintenance.

However, AI itself must be monitored to prevent new forms of system failure due to algorithmic bias or hallucination.

Prepare for Climate and Geopolitical Shifts

The future will bring more extreme weather, resource scarcity, and geopolitical instability.

- Build infrastructure to withstand higher temperatures, floods, and storms.

- Diversify supply chains to reduce dependency on conflict-prone regions.

- Develop decentralized energy and communication networks.

Resilience is no longer optional—it’s a strategic imperative.

What is the most common cause of system failure?

The most common cause of system failure is human error, often compounded by poor training, fatigue, or flawed procedures. However, in digital systems, software bugs and cybersecurity vulnerabilities are rapidly rising as leading causes.

Can system failure be completely prevented?

While it’s impossible to eliminate all risks, system failure can be significantly reduced through redundancy, proactive monitoring, robust design, and a strong safety culture. The goal is not perfection, but resilience and rapid recovery.

What is the difference between system failure and component failure?

Component failure refers to a single part breaking down (e.g., a server crashing), while system failure occurs when the entire network or process stops functioning due to cascading effects, even if only one component failed initially.

How do organizations recover from a major system failure?

Recovery involves activating emergency protocols, restoring services using backups, conducting a root cause analysis, and communicating transparently with stakeholders to rebuild trust.

Why is the Boeing 737 MAX considered a system failure?

The Boeing 737 MAX is considered a system failure because it involved multiple layers: a flawed MCAS software design, inadequate pilot training, regulatory oversight lapses, and a corporate culture that prioritized speed over safety—making it a perfect storm of technical and organizational failure.

System failure is not just a technical glitch—it’s a complex interplay of design, human behavior, environment, and culture. From power grids to software platforms, no system is immune. But by understanding the root causes, learning from past disasters, and building resilient structures, we can reduce the frequency and impact of these events. The key lies in preparation, transparency, and continuous improvement. In a world where everything is connected, preventing system failure isn’t just smart engineering—it’s essential for survival.

Further Reading: